Release time: 2020-07-14 14:31

How We See Ourselves in Our Fantasies, and What It Means

New research helps explain the deeper meaning of our sexual fantasies.

When you fantasize about sex, do you appear in your own fantasies? If so, do you appear as you do in real life, or do you change yourself in some way?

I studied the sexual fantasies of 4,175 Americans from all 50 states for my book Tell Me What You Want, and one of the many things I looked at was the way that we see ourselves. What I found was that many people change some aspect of themselves, such as their body, their genitals, or their personality. However, I found that different people change themselves in very different ways and that the types of changes people make seem to say something important about them. However, they also say something about our culture.

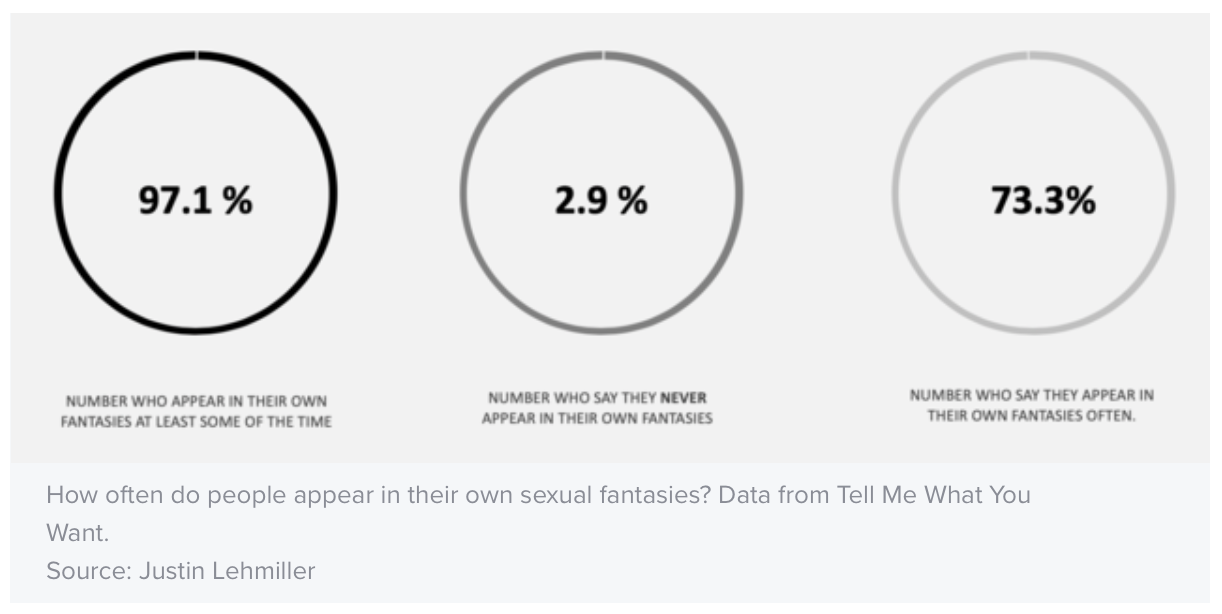

When I asked people whether or not they appear in their own fantasies at least some of the time, almost everyone (97.1 percent) said yes. Further, most people said they appear in their own fantasies most of the time.

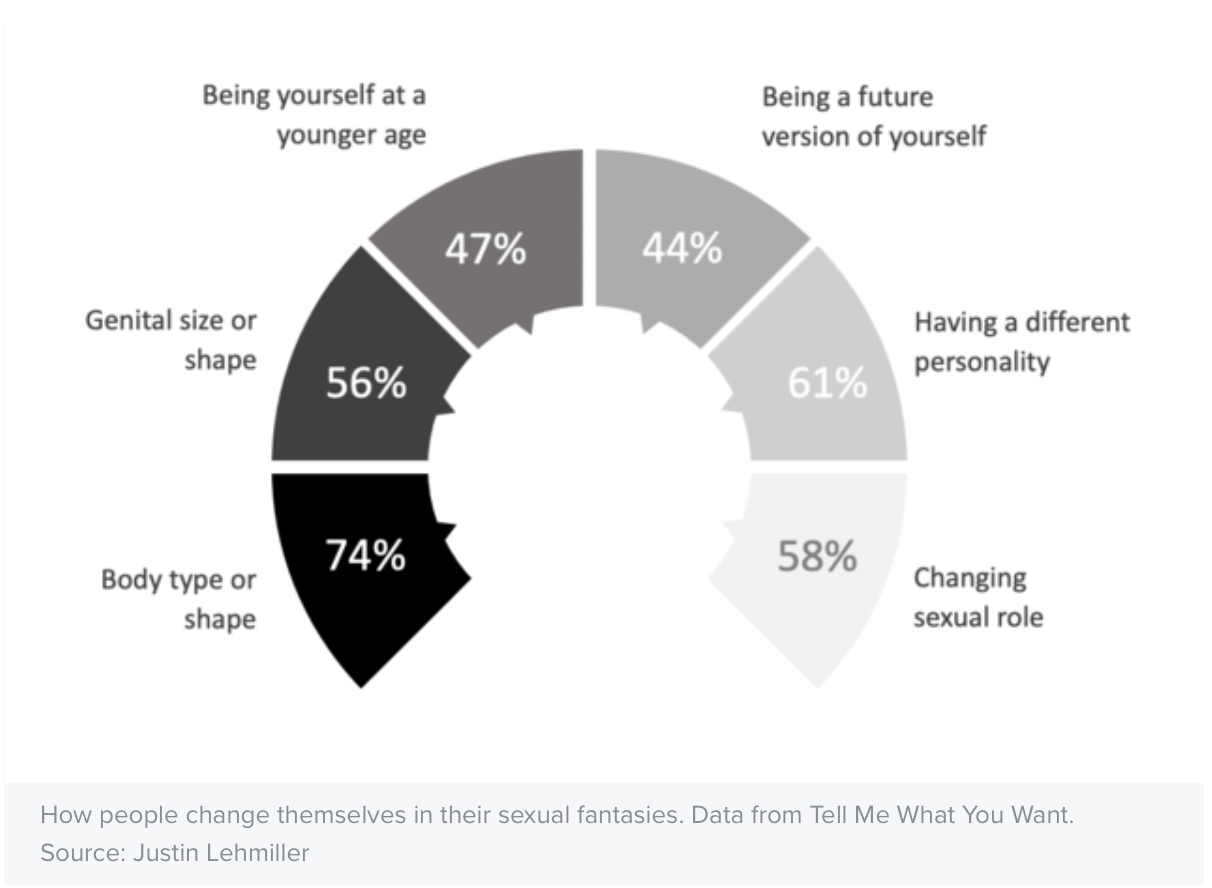

While most of us appear in our own fantasies, most of us see at least a somewhat different version of ourselves than exists in reality. A majority reported having changed their body type or shape, their genital appearance, their personality, and/or their sexual role (specifically, becoming either more dominant or more submissive). Nearly half also reported having changed their age, becoming either a younger or older version of the self. For specific numbers, see the figure below.

While changing oneself in one’s fantasies seems to be pretty common, I found that different types of people tended to change themselves in different ways. Notably, there were some pretty sizable differences across genders and sexual orientations.

For example, self-identified women (regardless of sexual orientation) were more likely to change their bodies than were self-identified men. However, gay and bisexual men were more likely than heterosexual men to change their bodies.

By contrast, men (regardless of sexual orientation) were more likely than women to change their genital appearance—but gay and bisexual men were even more likely than heterosexual men to do so.

When it came to age, men across the board were more likely to fantasize about themselves at a younger age, while women were more likely to fantasize about a future version of themselves. One of the most sizable differences I saw was that a majority of heterosexual men had fantasized about being young again, while only about one-third of heterosexual women said the same. Perhaps this is partly due to gender differences in sexual regret? Men are more likely than women to fantasize about missed opportunities, so maybe men are fantasizing about being younger more often because they’re revisiting past situations where they wished something would have happened.

When it came to changing one’s personality, gay and bisexual men were the most likely to report this—in fact, about three-quarters of them had done so, compared to about half of heterosexual men. Women (regardless of sexual orientation) fell in between.

Lastly, with respect to changing one’s sexual role, I looked at how dominant and submissive people said they were in reality compared to how often they fantasized about taking on dominant and submissive roles. The key finding that emerged there was that, among heterosexuals, women were more likely than men to fantasize about becoming more dominant than they actually were; by contrast, men were more likely than women to fantasize about becoming more submissive than they actually were. In other words, people were often breaking free of traditional gender roles and expectations in their fantasies.

With respect to persons who had non-binary gender identities, they were the group most likely to change themselves in their fantasies in almost all ways. The one exception was that they were less likely to fantasize about being themselves at a younger age. Why do non-binary folks change themselves the most in their fantasies? It may be because many of them are gender fluid—and if one’s gender expression changes in real life, one’s gender expression might also change in one's fantasies to reflect that. More generally, fantasies might also simply be a way for many folks to explore their gender expression.

What do all of these changes mean? As I discuss in Tell Me What You Want, they may say something about our personalities. For example, while introverted people fantasized more about changing their personality and becoming more dominant, extraverts were less likely to change themselves in any way. Neurotic individuals (those who don’t deal well with stress and who have more emotional instability) fantasized more about changing both their bodies and personalities. Interestingly, conscientious people (those who are more detail-oriented and organized) were the least likely to fantasize about changing any aspect of the self—their attention to detail appears to make them more likely to focus on the details in their fantasies.

Additionally, these changes may also say something about our attachment style. People with both anxious and avoidant attachment styles were more likely to change themselves in all ways. I suspect this is because the anxious folks (those who have abandonment issues) are soothing their concerns and becoming a version of the self that doesn’t have to worry about being rejected (I suspect the same is true in the case of neuroticism, discussed above). By contrast, I suspect the avoidant folks (those who have a lot of discomfort with intimacy) are literally becoming other people in their fantasies to create more emotional distance.

Lastly, these changes may say something about our culture. For instance, the fact that women changed their bodies more than men speaks to all of the media pressure that exists on women to be thin and to have a very specific appearance. Likewise, the fact that men were more likely than women to change their genitals may speak to the “bigger is better” messaging that men often receive through porn, which can give unrealistic expectations about what the average penis actually looks like.

Also, the fact that gay and bisexual men were more likely than heterosexual men to change almost everything about themselves (body, genitals, personality) may be explained by sexual minority men facing a lot of pressure to conform to masculine body and behavior ideals (the “masc 4 masc” phenomenon prevalent on gay dating apps).

With all of that said, it’s important to note that changing yourself in your fantasies doesn’t always have a deeper meaning—and it definitely doesn’t always reveal some type of insecurity. For example, people with very active imaginations often fantasize about changing themselves or becoming someone else simply because they fantasize more about almost everything.

As Sigmund Freud himself once famously said, “sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.”

Justin J. Lehmiller, Ph.D., is a Research Fellow at The Kinsey Institute at Indiana University.

psychology today